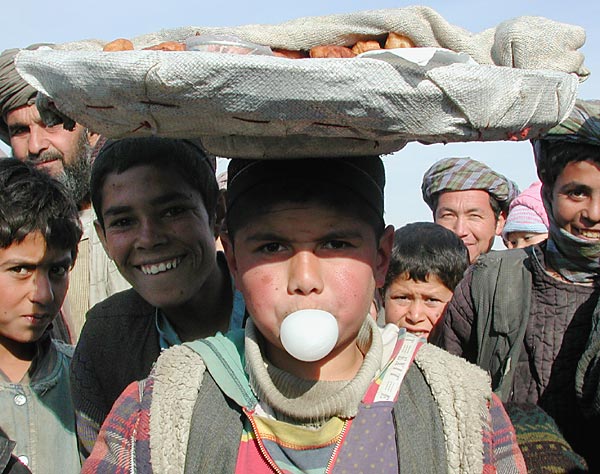

Afghan children have driven many cameramen and photographers mad: they always stare into the camera, very often making pictures unusable for a story.

I don’t blame them: for many, reporters were the first foreigners they had ever met and their professional gear was so different from what they had seen before.

Despite all the hardships that children share with their parents, they have not lost interest in life and are in high spirits most of the time.

They do pester foreigners for money, but when you tell them you are here to work, they normally switch to observing you instead. This means following you on the streets – and looking into your camera, television or still, whenever you point it at them or in any other direction. Video camera operators working in Afghanistan called it the “Afghan boy factor” and they tried to minimize its effect in two ways. One: they pretended they didn’t shoot, when they actually did, by looking into a different direction after turning on and pointing the camera at a street scene or a building.

This method did not work for all filming needs, plus the kids quickly realized the cameraman was trying to cheat. The second method was somewhat uncivilized: a translator was asked to exercise his “crowd-control” skills, which boiled down to a few short but loud exclamations, and that usually did the trick: the children got dispersed. The words spoken meant merely, “Go away, kids.” The secret was in the volume and anger levels in the translator’s voice.

All my translators, from Rakhmat to Abdul Bashir to Engineer Imran, were adepts of the technique. Abdul Bashir also applied it to Northern Alliance soldiers, but we quickly realized the danger and had to lie to him that it was OK for mujahedeen to follow our two-men filming crew and stare into the camera.

Afghan children begin to work almost as soon as they learn to walk. They tend crops in the fields, carry merchandise to a bazaar, look after smaller brothers and sisters. Afghan families are usually large, up to ten children, which is essential for survival.

Boys and girls are often seen on the roads in Northern Afghanistan, picking up stones that keep rolling down the mountain slopes.

Motorists are supposed to give some money for this work and, in fact, great help to them on the road, but the practice should really be banned because many kids were run over by passing vehicles as they tried to fetch Afghani banknotes thrown to them by drivers out of their car windows. Because of the dire poverty that affects the majority of the population, most Afghan children have no toys: at least I didn’t see any in families that I visited in the Panjsher Valley and elsewhere in Northern Afghanistan. Stores do have a limited assortment of balls and dolls imported from Pakistan and China, but there is definitely no market for them yet in the impoverished country. Nor apparently is there any market for children’s clothes: boys and girls follow the dress code of their fathers and mothers, except that small girls don’t yet have to wear the burqa. Tailors have an easy life, churning out clothes of the same pattern, just different sizes.

Some boys like to wear woolen hats, known as pakul, while others prefer turbans or skull caps, but that’s all as far as variety goes.

Often, the choice of headgear depends on local customs and traditions. All boys, as well as men, sport long cotton tunics and matching loose trousers, accented by black boots or sandals. This attire is very comfortable for hot Afghan summers, and many foreign journalists bought ready-made pajama sets or ordered them at numerous tailors’ shops. On the negative side, they got soiled too fast, compared to jeans and T-shirts that were easier to wash, so the fashion never rooted in. Afghan girls wear brightly colored dresses complemented by long pants, and head scarves and sandals to match. Socks are rare. In summer time, it is not uncommon to see children, as well as grownups, walking around barefoot. Whether this was out of poverty or because of the natural aversion for the smell of sweaty feet, I never figured out. Unlike in the United States, but very much like in Russia or Korea, people in Afghanistan take off their shoes when they enter a home. Shoes are left outside, so don’t be surprised when you find unisex slippers instead of your favorite sneakers or high heels. Footwear, like rosaries, have no owner in Afghanistan. I lost two pairs of boots in this way after leaving them thoughtlessly outside our dining room in Jabal os-Saraj. The boots were not really stolen, somebody just put them on and walked away, leaving behind plastic sandals, which were as good as new.

Back to the children, though. Girls in ethnic Turkmen families in Balkh Province are famous for their skill of weaving beautiful and expensive carpets. The business is so lucrative that when the time comes for a daughter to get married, her parents demand thousands of dollars in dowry money from the prospective groom’s relatives.

The latter usually don’t bargain because they appreciate their future daughter-in-law’s money-making potential: a woman can weave a carpet with a street value of 400 U.S. dollars in one month. That’s more than a fortune.

Afghan men (and probably women, too) like to make fun of small kids. The most popular and apparently funniest joke runs as follows, “Are both your Dad and Mom Muslims?” Ha-ha-ha. I heard that “joke” many times in Afghanistan, and it reminded me of a question, meant to be jocular but sounding very stupid, which is often asked in similar circumstances in Russia, “Whom do you like more, your Dad or Mom?”