Alexander Merkushev

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

The telephone in my apartment rang at about 3 a.m. Monday.

The chief of the Russian-language news service told me that the Tass deputy director, Gennady Shishkin, had ordered a team of correspondents and translators to report immediately. A car was already waiting outside to take me to Tass headquarters in downtown Moscow.

The morning was quiet, but that proved to be deceptive.

Three or four editors and I, standing in for the entire English-language service, waited to hear from Shishkin directly. All we knew was that we were going to transmit ”a very important” story-in fact, several state documents. Confused and intrigued, we argued about what that story might be. After a couple of cups of coffee we realized that the date was Aug. 19, the eve of the signing of the new union treaty.

We thought perhaps the Communist Party had a secret meeting Sunday and decided to remove Mikhail Gorbachev as its general secretary. Nothing less, we argued, would have warranted piping all hands on deck in the early hours of the day.

As things turned out, it was far worse.

About 5 a.m., Shishkin said he had the documents. Purportedly they were delivered to Tass by the then-head of the government radio and television company, Leonid Kravchenko, who apparently had gotten them directly from the coup organizers.

Radio and Tass were told to start transmitting the documents simultaneously at 6 a.m.

I looked through the papers, and I fully realized what the expression ”to lose heart” means. Even though democracy was only a baby, we had somehow gotten used to its durability, and the announcements by the self-appointed Emergency Committee seemed surreal, totally out of this world.

Attached to the package were instructions on the order of transmission-put very politely, to my surprise, considering the contents. It said, ”We request that the materials be transmitted in the following order:

1. Edict by Vice President Gennady Yanayev.

2. Statement by Chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet Anatoly Lukyanov.

3. Acting President Gennady Yanayev’s Address to Heads of State and Government and the UN General Secretary,” and so on.

I was convinced that a coup had taken place and that its authors were merely stating the fact. I visualized the internment of Gorbachev, the arrest of Russian President Boris Yeltsin and all the radical deputies who emerged in the years of perestroika.

For a fleeting moment, I considered warning someone about the coup. Police? They are apparently on the plotters` side. The Russian authorities? By now, they must have been all under arrest or even executed. Foreign correspondents? Then it would not be me who would break the news.

My hands still trembling, I managed to translate the first announcements. At 6 a.m. sharp, following the customary playing of the state anthem, a radio announcer began to read Yanayev`s edict. We followed suit.

The idea of a military coup in the Soviet Union was so unbelievable that some Tass foreign correspondents later told me they thought it was a joke by the English service. Some joke.

Later that morning Tass journalists began to notice strange things.

Shishkin, who was standing in for vacationing General Director Lev Spiridonov, refused to authorize the release of any stories, leaving all decisions to the rank-and-file news editors. They considered moving the highlights of the State of Emergency edict only to realize that the Emergency Committee effectively violated not only the constitution, but the very law it had referred to in declaring martial law.

Gulag fears were evoked. This and similar stories were put on hold as orders from above Monday afternoon began to clearly indicate the path to tread.

One of the orders was to report ”positive” reactions to the coup. In the absence of these, some correspondents, unwilling to make up outright lies, resorted to the old Tass trick of picking favorable bits out of generally negative or ambiguous comments. Many, however, sent dispatches based on factual material that were-surprise, surprise-transmitted almost unedited. There were no military censors looking over our heads.

Toward evening, Spiridonov cut short his vacation and returned to Moscow. To his credit, he told us only to report facts and to try not to incite violence.

Even television, the prime vehicle for conveying ”decrees” to the public, made an attempt to present two sides of the story. Television journalists later said this resulted from an oversight by their superiors.

But the best source of information was the independent radio station Moscow Echo. Its live reporting and news updates were interspersed with calls for civil disobedience and even instructions on what to bring for the all-night vigil around the Russian parliament to protect the republic’s legitimate government.

Throughout Tuesday, Tass transmitted ”official” documents from the self-appointed rulers and reports about the response to the coup from Moscow and provinces, and from abroad. Their overall reaction was, of course, negative.

Many Moscow-based foreign correspondents called the office, asking if we knew something that made us so bold or if we had some instructions to express our opposition to the coup. The situation, however, was far from clear.

Only a handful of newspapers, all run by the Communist Party, were allowed to appear. But independent journalists did not remain silent. They pooled resources and on Tuesday published the Common Newspaper. Printers at the newspaper Izvestia agreed to print the junta`s edicts only after editors added Yeltsin`s address to the public.

On Tuesday night the military imposed a curfew. The Tass deputy general director, Anatoly Krasikov, ordered the news service to close down at 11 p.m., the curfew hour, and told all employees to go home.

But troops failed to seize the Russian parliament that night, and the plot began to fall apart.

With the new printing and copying technology, the new rulers were unable to control the printed word. Thousands of leaflets were pinned on walls of buildings, distributed among soldiers controlling major intersections of the Soviet capital. Western radio stations also helped fill in the facts.

Wednesday morning, Tass was moving stories that ranged from staid statements by the Moscow military commandant and reports about the KGB’s successes in fighting crime to downright condemnations of the new regime from USSR regions and public organizations, and Western leaders. By 5 p.m. Tass considered the coup over.

First the English-language service put quote marks around the name of the emergency committee-Tass’ ultimate indication of disdain. Another story called the coup leaders ”the former State of Emergency Committee”- even though the situation remained unclear.

Wednesday night, Gorbachev was quoted as saying the situation was under his control. All restrictions on the press were lifted.

Yeltsin announced that state radio and television were transferred to the Russian government’s control, and immense pressure was being brought on Kravchenko to resign.

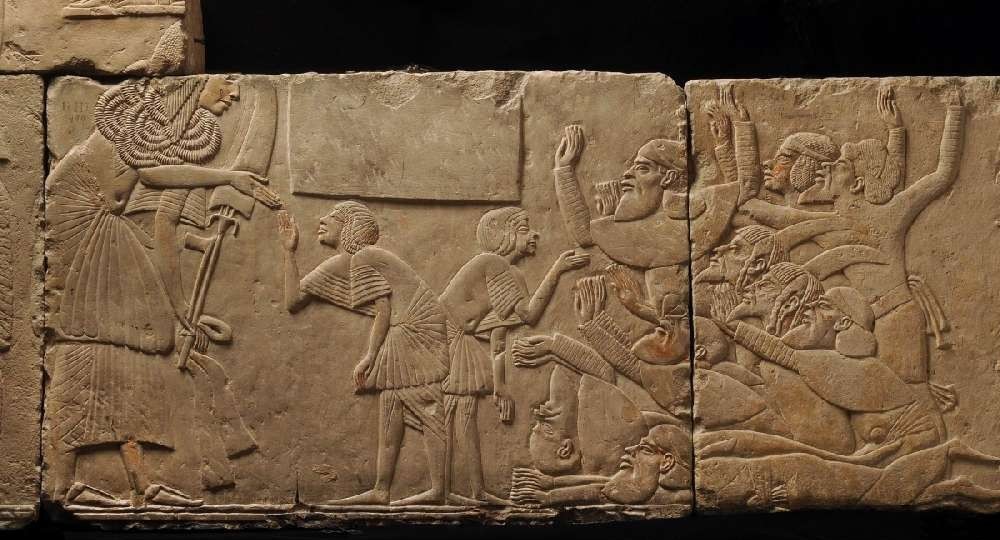

The featured image shows Boris Yeltsin addressing his supporters (Photo by Andrei Babushkin / TASS)